Reassurance

I don't know what to say to be a comfort or what to do to be useful.

I don't know whether to pick up the phone and call, or send an e-mail, or buy a card, or write a letter.

I don't want to intrude, or overstep, or upset anyone.

I'm sure I'd call at the worst possible moment—when the person is on the other line with the funeral home, or has finally drifted off after a sleepless night, or is just sitting down to the first decent meal in days.

Or I think that I've been out of touch too long, and that it would be inappropriate to reach out now, at such an awful time.

Being on the other side of it for the past week, I have a new perspective on the situation.

I've been touched to receive calls and e-mail messages and cards and personal notes.

I'm grateful for visits from friends and family and neighbors, whether they are people I see to all the time or haven't heard from in years.

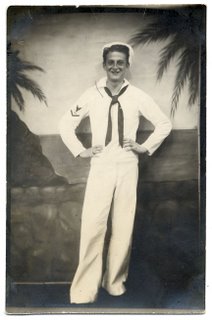

I'm delighted to hear old stories about my dad that are new to me—and that instantly confirm something I always knew or suspected about him.

All of these are a comfort, and all are a welcome distraction.

If I can share the wisdom I've recently acquired, it is this:

There is no "right" way to convey your condolences.

You can call, or write, or visit, or make a donation, or send a care package, or attend the funeral service—they are all the right things to do, and it doesn't matter which one (or ones) you choose.

It doesn't matter if you are eloquent or awkward in the process. You will likely be both.

What matters is that you reach across the void—in whatever way feels right—and let the other person know that you, too, feel this loss.

You may feel it directly, if you were close to the person who died, or you may simply empathize with the friend or loved one who has suffered the blow.

Either way, you are offering psychic solidarity.

You are lending strength, providing comfort, and, above all, sharing your humanity.

Whatever you do, it will make a difference.

Trust me.